Chapter 3: Restoration Efforts and Institutional Environment

As Paris’s outward expansion began to infiltrate the Bièvre valley, support for protection of the natural environment grew. Awareness of the stream’s annihilation in Paris and its immediate suburbs undoubtedly catalyzed restoration efforts upstream. The evolution and nature of these efforts through the turn of the 21st century are critical to current plans to restore the stream’s Parisian stretches. These plans will be examined in Chapters Four and Five. This chapter will explore the restoration movement and the institutional environment in which it developed. The gradual accumulation of influence by the region’s associations is among the most noteworthy. The second part of the chapter will consider the nature of restoration projects in order to gauge their atonement for the destruction of ecological functions. The influence of these projects on the Bièvre’s restoration in Paris will be ultimately implied.

Regulatory Context

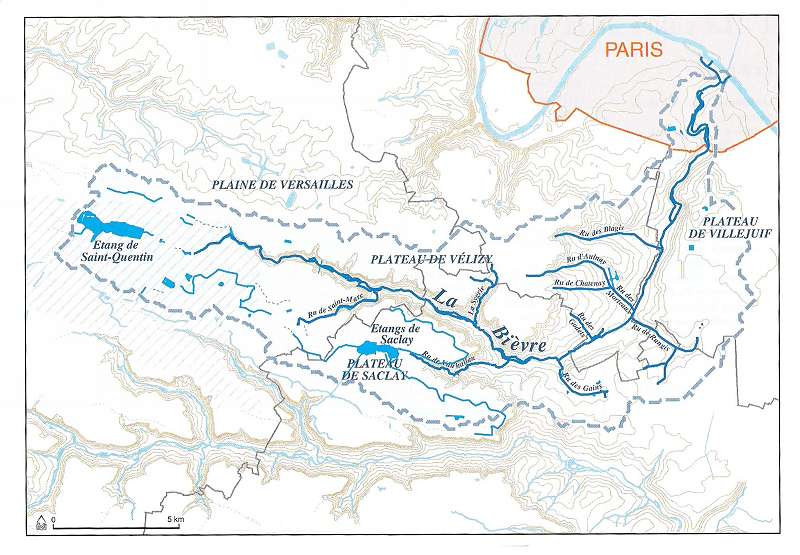

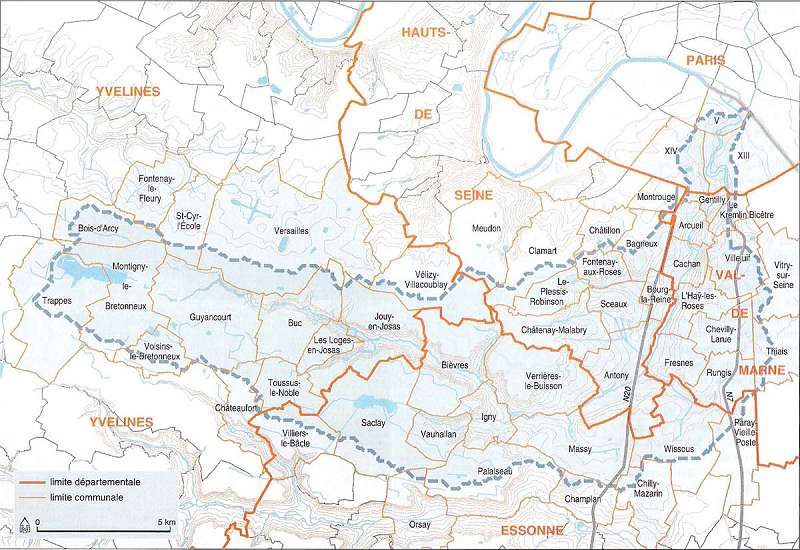

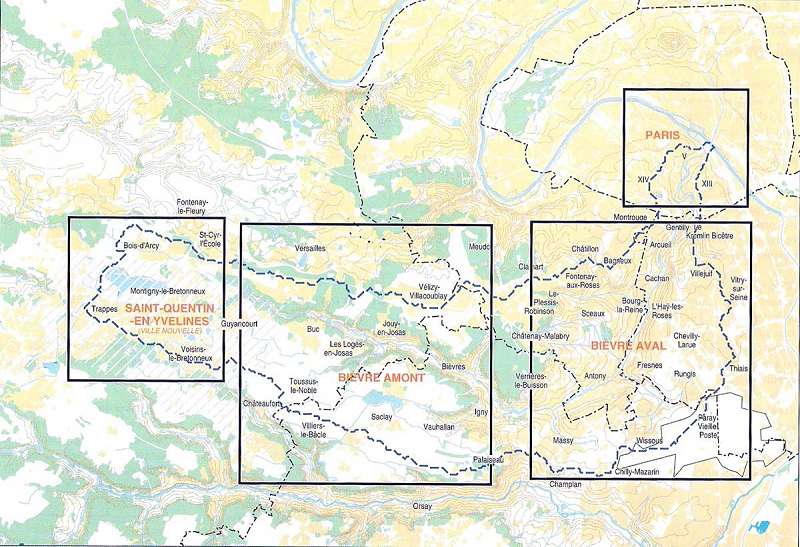

The Bièvre exists within a regulatory environment defined by the administrative division of land into departments and communes. The Bièvre crosses five départements within the Ile-de-France region from southwest to northeast: Yvelines, Essonne, Haut-de-Seine, Val-de-Marne and Seine. Each department is composed of communes containing a town hall and a mayor charged with the commune’s planning, with the exception of Seine, or Paris, which is divided into 20 arrondissements. The Bièvre in Paris concerns only the 13th and 5th arrondissements, which have political jurisdiction similar to communes.

The Bièvre Valley Watershed is often examined with respect to four different geographical zones. The most western section constitutes the new town of Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, composed of seven communes with a density of 2,610 inhabitants per square kilometer. Moving east, the rural section contains eight communes with a density of 570 inhabitants/km2. The next section can be characterized as a zone of transition, extending from the city’s green belt with a density of 2,420 inhabitants/km2 in five communes. Finally, the last zone includes fifteen communes south of Paris as well as the city’s two arrondissements with an average density of 8,400 inhabitants per square kilometer.

The administrative limits of the communes and départements within catchment area

(Conseil Régional)

The Bièvre Valley divided into four segments with respect to population density (Conseil Régional)

Examination of the Bièvre’s historic hydrological structure reveals the degree to which the watercourse and its watershed have been altered over time. The present state of the stream bears no resemblance to its historic course from Antony to the Seine in Paris, which has considerable implications for restoration efforts. The Bièvre’s last few kilometers within Paris were the most drastically altered, its flow replaced entirely by sewers and collectors; its bed buried in embankments. Just outside Paris in its immediate suburbs, all of the Bièvre’s water was diverted to treatment plants near the Seine by 1953, their meanders straightened and streambeds covered within a decade. Increased urbanization in these areas has since given rise to flooding problems along the Bièvre’s tributaries. Replacement by pipes and diversion towards the same filtration plants has lead to total infrastructurization of the stream’s lower water shed.

Land-use along the Bièvre is influenced at both regional and local levels. The Conseil Regional d’Ile-de-France (Regional Counsel) and the Agence de l’Eau de Seine Normandie (Water Agency of Seine-Normandy) are the two primary actors in regional plans and initiatives. Locally, several public agencies oversee development in the Bièvre Valley in addition to the mayor’s office of each commune. The sanitation syndicates of the Bièvre Valley (SIAVB) and the Parisian Agglomeration (SIAAP) as well as the New Syndicate Agglomeration (SAN) and Community Agglomeration of Val de Bièvre are all public agencies representing the interests of numerous communes. Outside government, nearly 50 associations make up a collective called the Union Renaissance of the Bièvre. Among the diverse associations represented is Les Amis de la Bièvre (Friends of the Bièvre), the first environmental association created for the Bièvre’s protection in 1962.

The Bièvre Valley: Origin of Restoration Efforts

Efforts to manage the quality of the natural environment in the Bièvre Valley began with the creation of the Syndicat Intercommunal d’Assainissement de la Vallée de la Bièvre (SIAVB, Intercommunal Sanitation Syndicate of the Bièvre Valley) in 1945. For two decades SIAVB managed solely sanitation issues along the Bièvre from Buc to Massy. Upon the creation of the new town of St-Quentin-en-Yvelines, the syndicate expanded its role in confronting the consequences of the new town. As early as 1982 it developed an anti-flooding program in response to the over-urbanization of the Valley. The Bièvre’s location downstream of urbanized and impermeable land, its course through the valley’s towns, and its slow rate of flow made it particularly vulnerable to pollution. SIAVB’s concern for this problem spawned its first regional contract to construct retention basins permitting the absorption of rainwater and its gradual release to treatment plants. Such efforts resulted in a rapid improvement of the Bièvre’s water quality and its ability to foster marine life. Overall improvement in water quality over a 10-year period has attracted public interest in the stream and spawned numerous revalorization and restoration projects. Among them, SIAVB opened a 1.4 kilometer stretch of the Bièvre in Verrières and Massy in 2000. Success of this project has come from careful phasing in coordination with the communes.

The Syndicat Intercommunal d’Assainissement de la Vallée de la Bièvre has maintained an important role in assuring good water quality within the twelve communes traversed by the Bièvre for several decades. Its strict monitoring of all tributaries of the Bièvre has considerably increased its control over the Bièvre’s rate of flow while its involvement in local development permits it to advocate for run-off management in all new construction. To this end, SIAVB has begun buying land along the Bièvre to favor the expansion of flood waters and the creation of pedestrian paths. According to its director, the syndicate’s projects are emblematic of intelligent management of urban streams in the future where streams like the Bièvre assure the liaison between the natural and urban environments. SIAVB has become involved in projects outside its territory in the interest of advancing its cause in permitting upstream waters to reach the Seine. It has mastered its terrain and now seeks to aide in the restoration of the rest of the stream.

Environmental activism around the Bièvre began with the foundation of Les Amis de la Bièvre in 1962, whose primary objective was to protect the valley of the Bièvre from development that would degrade the quality of its stream. Over the years, private contributions to the association enabled it to prevent and/or influence industrial developments within the vicinity of the valley, as well as fight off several proposed extensions to the Paris’s peripheral highway. As these efforts continued, more and more people along the stream became involved in safeguarding the Bièvre and its environs. The development of an annual walk in 1981 by two seventeen year-olds was one of the most successful efforts in raising awareness for the conservation and maintenance of the Bièvre. In 2004, despite a constant rain, over 1000 people participated in the fifty-kilometer walk from Paris to the stream’s source.

|

|

Former logo of the Friends of the Bièvre Valley (left) and Publication of 30 years of history of the Bièvre Valley in light of the defense of its environment by the Friends (right) |

|

As the efforts of the Amis de la Bièvre have progressed, the water of the Bièvre has slowly been reanimated with recreational fishing. With the Bièvre valley’s constant risk of inundation with new developments, AVB helped obtain classification in 1991 protecting the stream and its corridor from development. Such accomplishments are partly due to the Friends’ collaboration with SIAVB, which has grown stronger in recent years. Like the Syndicat Intercommunal d’Assainissement de la Vallée de la Bièvre, the Amis de la Bièvre have become involved more and more in the stream’s path closer to Paris, beyond the rural section where it originated. This involvement will be examined later in this chapter.

Antony to Paris: Slow to annihilate, slow to restore

The modification of departmentalization of the Paris region in 1964 spawned the creation of a regional sanitation agency, the Syndicat Interdépartemental d’Assainissement de l’Agglomération Parisienne (SIAAP, Interdepartmental Sanitation Syndicate of the Parisian Agglomeration) in 1970. This agency supervises a territory of 1980 square kilometers where it operates four water treatment plants treating nearly three million cubic meters of water per day with a population of 8.4 million. Its objectives are to protect the natural milieu, transport and purify urban waste water, treat and enhance sludge and study, realize and exploit transport and treatment works.

The Interdepartmental Sanitation Syndicate of the Parisian Agglomeration plays a major role in the restoration of the canalized Bièvre from Antony to Paris. All works constructed along this course were inherited by the syndicate upon its creation in 1970. Despite the projections made for the future, the rapid urbanization of the area rendered most of the projects insufficient. Retention basins were rebuilt or expanded and sewers and collectors were widened or doubled following the first hydraulic study of the Bièvre Valley by the syndicate from 1974 to 1977. Another study and regional plan of the Valley was performed from 1989 to 1993 which proposed several new hydraulic works. The study of hydraulic functionality of 1996-97 concluded that increased urbanization would render problematic the capacity of structuring networks within 10-15 years if nothing was done to master new intake. As observed elsewhere in the Parisian agglomeration, increased urbanization was overburdening the system of water management and treatment. Two studies conducted by SIAAP in the late 80s and again in the mid-90s concluded that the deficits in the capacity of the system in part due to "secret branches" made the separation of rain and waste water nearly impossible. This conclusion remains the major obstacle for contemporary restoration efforts along the Bièvre between Antony and Paris. Nonetheless, in the valley is home to the Antony sanctuary; a retention basin created in the 1930s and classified a Zone naturelle d’intérêt écologique, faunistique, floristique (ZNIEFF, Natural Zone of Ecologic, Faunistic and Floristic Interest) in 1986. The Antony wildlife sanctuary and retention basin occupies six hectares and is home to over 150 species of birds within a highly urbanized context.

Combined Efforts for the Bièvre’s Restoration

In 1984, the Conseil Regional d’Ile-de-France (Regional Council of Ile-de-France) adopted a project to reopen the Bièvre and urge "its participation in the urban landscape". While the upstream segment was under control, the Antony-Paris segment faced two technical problems, the depollution of water and the regulation of its flow. Two studies were conducted, one on sanitation by a regional water and sanitation agency, and the other on the stream’s integration into five of the valley’s communes, conducted by landscape architect Alexandre Chemetoff. The first of its kind to concern the restoration of the Bièvre within an urban setting, Chemetoff’s study presents two different approaches to restoring the Bièvre; one through daylighting and the other through the use of evocative techniques. The areas identified for daylighting were part of a long-term plan that envisioned segments of the Bièvre emerging from its collector to enhance the public realm. Areas free of development, such as public parks or squares would be capable of receiving Bièvre water once its sanitation was mastered. In areas where the stream’s daylighting was impossible due to infrastructure obstructions, however, Chemetoff suggested highlighting its passage with special treatment.

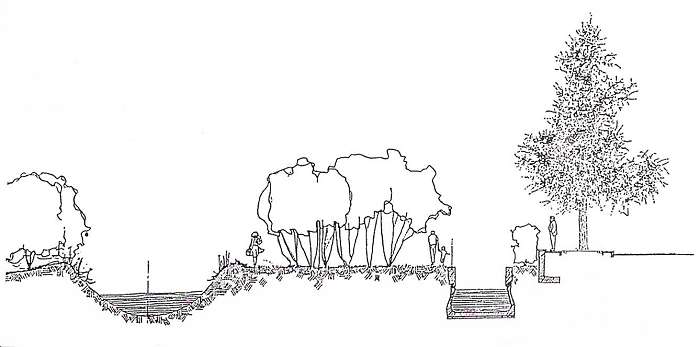

Chemetoff sketch showing canal parallel to Bièvre collector, supplied by rain water to function as a retention basin. Eventually, after the Bièvre water’s treatment, it could be uncovered and its water diverted into the new canal.

Chemetoff also called for the preservation of stream heritage and a moratorium on new building within the stream’s former path. Chemetoff further developed this idea in a 1991 plan, designating the Ginkgo biloba and motif street furniture as a means of evoking the stream’s memory. While some of these evocative techniques were realized in the early 90s, the parcels restricted from development are only now beginning to be redeveloped. The Park des Prés in Fresnes is among these and will be examined in detail with respect to its ecological approach in the next section. Chemetoff’s objective was to reestablish visual coherence in the landscape where transportation infrastructure left only fragments of continuity. This coherence was projected for the future and based on local topographical characteristics for the ensemble of the valley, but it did not envision a complete opening of the Bièvre along its course.

The Syndicat Intercommunal d’Assainissement de la Vallée de la Bièvre’s competence and reputation in the field allowed it to expand outside its territory in the interest of permitting upstream waters to reach the Seine. In order to improve the state of the Bièvre between Antony and Paris, an ensemble of residents who live along the Bièvre decided to coordinate their actions to create a five year program, the "Contract of the a Clear Bièvre Basin" in 1997. At its completion in 2001, a development plan for water management in the Bièvre basin, from source to mouth, was declared imperative. In 1999, SIAVB was selected by numerous agencies, including the Conseil Régional, the Agence de l’Eau de Seine Normandie, the Ville de Paris, and the Syndicat Interdépartemental d’Assainissement de l’Agglomération Parisienne, to complete a feasibility study of the opening of the stream along its course to Paris. Titled "Reopening of the Bièvre," the study responded to "a pressing demand of residents wishing to see water in their towns".

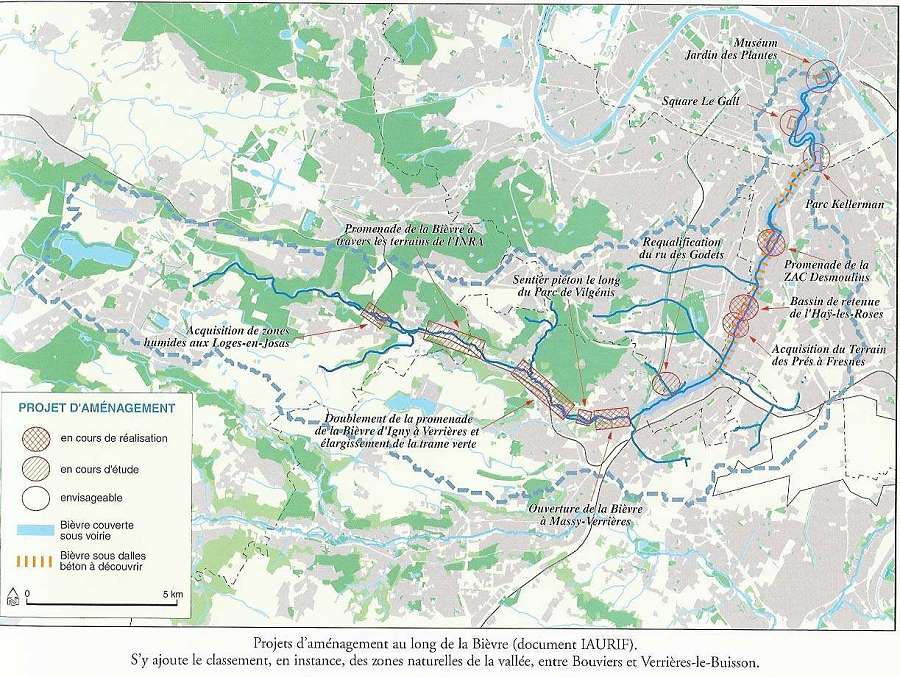

"The Reopening of the Bièvre" has two objectives: to determine the possibility of disconnecting the Bièvre downstream of Antony from all sources of pollution and to establish the potential transfer of clear, good quality water from upstream to the Seine. It builds on Chemetoff’s study in that it establishes the technical feasibility of daylighting the Bièvre on the most easily developed sites within a period of less than ten years. Similarly, it proposes two different approaches of varying scope. The first proposes the total reopening of the stream within a vegetation-lined stream bed with an opening of fifteen meters, achievable in the long term over twenty-five years. The second, more realistic and pragmatic, recommends the conservation of the present functions of state-owned water line, the Bièvre Collector, while creating parallel reaches in liaison with the Bièvre via gravity, pumps or siphons. These new reaches would take the form of meanders accompanied by small ponds containing macrophytes that would serve as auto-purifiers. Where space was not available for such treatment, water could pass from the collector to the reach via dépollution chambers capable of trapping hydrocarbons.

|

|

|

The Agence de l’Eau Seine Normandie proposed in 2002 a group of elements for a sustainable sanitation policy in the Bièvre Valley. The policy insists on the necessity of limiting the intake of new water from streams and run-off into the sanitation system. It includes controlling impermeable surfaces, separating wastewater from runoff, limiting urban growth, and acknowledging the solidarity of upstream and downstream. SIAAP studied the application of this policy in 2002 in relation to the hydraulic functionality of the Bièvre Valley when it rains. It concluded that future developments have the potential to greatly improve the struggle with minor flooding due to overflow, limit run-off from impermeable zones, and with respect to the Bièvre, close connections between the stream and those works that do not separate wastewater from run-off. This resulted in SIAAP’s creation of a charter known as Bièvre Aggravation Zero that called for an end to increases in the rate of flow within the entire Bièvre water shed. This charter would become essential for all stakeholders, especially the mayors of each commune in charge of urbanism. In order to implement it, SIAAP confirmed the need for all local and regional governing bodies to assist in the financing of projects.

On the municipal level, the Agglomeration Communauté de Val de Bièvre (Community Agglomeration of Bièvre Zalley) was created in 1999 as an intercommunal public establishment of seven communes located between Antony and Paris: Arcueil, Cachan, Fresnes, Gentilly, L'Haÿ-Les-Roses, le Kremlin-Bicêtre and Villejuif. United around projects within their territory, the agglomeration enables these seven communes to collaborate on economic development, urban politics, land-use planning, infrastructure, water and services. Its mission is to improve the life of the 185,000 inhabitants of the Val de Bièvre by working collectively on concerns that exceed communal limits in order to be more efficient and influential. Their dedication to the reopening of the Bièvre has produced projects such as the Parc des Prés de la Bièvre in Fresnes. This project includes the reinstallation of the Bièvre in its former stream bed which will eventually support the totality of its flow. The recreation of its meander will increase the diversity of its surroundings. It would not have been possible without the sanitation efforts of the past 15 years, which brought improved the water quality to enable such a project.

The creation of the Syndicat Mixte de la Bievre (Mixed Syndicate) for the entire length of the Bièvre has been envisioned since 1999 by the Conseil Régional d’Ile-de-France. This syndicate targets the Bièvre watershed, described as uniting all tributaries and all spaces whose slope converges with the Bièvre’s stream bed. It includes all actors, both passive and active, and exists to favor concertation and planning. One objective is to create a regional planning and development plan for water to orient development in the future. The Regional Counsel of Ile-de-France launched the idea of creating the Mixed Syndicate in 2001 but it has yet to be fully created. Its objectives are the reopening of the Bièvre from Antony to the Seine with its own water, the renaturation of the stream, the protection of natural patrimony, the rehabilitation of patrimony linked to water, the protection of all in view of urbanization, the study of the stream’s jurisdiction, and to serve as a common home to all the different actors involved in the Bièvre: State, Regions, Departments, Communes, Associations, Businesses, Syndicates.

The Union des Associations Renaissance de la Bièvre was created in 1999 as an association representing a common interest of numerous public, private, and non-profit agencies and associations located in the Bièvre Valley. Their constitutive charter lays out the priorities for the citizens living and working along the Bièvre as to preserve and restore the Bièvre. According to this charter, the associations and organizations agree that:

Like all rivers of France, the Bièvre has a judicial right protecting its flow and adjacent banks from development. Since 1992, all water bodies in France are protected from new development, which must be approved based on its environmental impact by the Ministère de l’Environnement et Développement Durable (Minister of the Environment and Sustainable Development). As some parts of the Bièvre are covered and some parts are just dead reaches containing no water, however, the regulations are complicated to apply. Nonetheless, the strict application of the law is important for the stream’s borders, with four meters of protection on either side, and larger adjacent protection to prevent construction. The land-use plans are an important stake to which municipalities pay more and more attention. The Bièvre basin is designated in the inventory of protected sites since 1972 at the request of the associations. Since 1995 part of the rural portion is a classified site. The valley was inscribed to the inventory of protected sites in 1971 and the classification of all natural zones was decided in 2000.

The main discrepancy between the actors is that open-air part of the Bièvre is publicly owned and accessible while the buried part is owned by a sanitation network. SIAVB and the associations work towards ameliorating the stream’s water quality while the same water downstream is transported by a combined water system to a wastewater treatment plant. While the syndicates have the common objectives of cleaning the water within the Bièvre basin, only SIAVB has been capable of achieving this so far. The sanitation network of the Syndicat Interdépartemental d’Assainissement de l’Agglomération Parisienne remains a major obstacle. Its responsibility is especially important when considering the opening of the Bièvre in Paris, which would require clean water.

Reflections on Ecological Approaches to Restoration Projects

The success of the associations and agencies in restoring the Bièvre created the momentum responsible for present day efforts to recreate the stream in Paris. Using ecological functions as a measure of successful stream restoration, recent projects between Antony and Paris may serve as indicators of the kind of approach to be expected in Paris. While introducing ecological functions appears to be a priority of the new syndicate and the Union, the projects that have been realized are not all incorporate these functions. For example, a small portion of the Bièvre’s water was taken out of underground collectors in Verrières in order to create a small bucolic meander along a pedestrian way by the Sanitation Syndicate of the Bièvre Valley. A portion of the original stream bed was exposed in Cachan to enhance a public open space by the Sanitation Syndicate of the Parisian Agglomeration.

In a paper titled "Urban as Landscape Infrastructure," French landscape architect Georges Farhat examines the evolution of the Bièvre Valley from Antony to Paris. He highlights SIAVB’s recent criticism of Chemetoff’s 1989 plan for containing "no hydraulic or ecological foundation but the idea to increase the awareness of different actors around the stream’s reopening." In the 15 years since Chemetoff’s plan, ideas about the feasibility of opening the Bièvre along its urban course have advanced considerably. As described previously, current plans entail the reopening of several sites along the Antony-Paris axis. Despite this, Chemetoff’s plan is still relevant, for what it called for in the long term is now taking shape with work such as the Park des Prés in Fresnes.

The new park in Fresnes, initiated by the Agglomeration Val de Bièvre, contains a 200-meter meandering stretch that siphons water from the Bièvre Collector, filters it, and releases it within a three-hectare park. This space provides potential as a retention basin in periods of inundation. According to one of the landscape architects responsible for the design, "the project was a question of giving back the stream its liberty…the space today provides a place of respiration in the middle of the town". The project aims to improve water quality, recreate the stream bed and "natural" banks, and transform a brownfield into a landscape providing several different environments. The project’s challenges/objectives included:

The Agglomeration Val de Bièvre received the Grand Prix de l’Environnement among the cities of Ile-de-France in 2003 for this "innovative, remarkable action" and for its political engagement in the environmental domain. In light of the measures of successful stream restoration described in Chapter One, the project’s true success is dependent on the continuation of similar efforts towards establishing continuity.

|

|

|

Sketches of Parc des Prés in Fresnes showing meandering Bièvre achieved with the help of siphons

The opening of the Bièvre in Massy and Verrières by SIAVB involves an approach similar to that used for the Parc des Prés in Fresnes. Here a constant amount of water from an underground collector of the Bièvre is released into a newly built streambed where it flows for a few hundred meters before reentering the collector. The banks are lined with grasses and reeds and marine habitat is slowly emerging. Due to the narrowness of the barrier between the stream and a parallel street, run-off flows directly into the stream without much of a buffer. While the stream provides an attractive roadside amenity for dog walking, it is not ecologically-functional. This project consequently should not be considered a successful urban stream restoration, as its accommodation of ecological functions is very limited.

|

|

|

Georges Farhat refers to the landscape approach being applied to the new projects along the Bièvre, equivalent to filling in segments of nature into the urban fabric, as kitsch. He instead favors Chemetoff’s scheme for a system that would mark the terrain, thus improving public awareness and freeing up spaces along the Bièvre for future projects. However, this ignores Chemetoff’s intentions for the future. In the fifteen years since his plan’s creation, some parcels have become developable and groups such as the Agglomération Val de Bièvre have become involved in doing just that. While such projects as the Park des Prés may be kitsch now because they rely on mechanical systems to clean and pump water, they continue to mark the traces of the Bièvre and as part of the long term contribute to the Bièvre’s greater continuity in the future. Ignoring that ecological integrity can’t happen over night, Farhat insists that "we’re creating stains of green earth linked to infrastructure". Open spaces are construed as zones against intensive urbanization, which should continue to be encouraged along the Bièvre.

The challenge is distinguishing between the projects whose objectives are purely aesthetic and kitsch and those whose objectives appear kitsch yet are part of a long-term plan of ecological achievement. One major factor in distinguishing between these two types is assessing the terrain to determine the feasibility of an ecological restoration. Another factor is examining if false hope is perpetuating the myth that the stream will one day be reopened in its entirety. Would projects like the Park des Prés be created otherwise? Should the Bièvre be used to garnish pocket parks that will never be part of a larger continuous stream system?

Evaluation of the ecological intentions of the work carried out until now on upper reaches reveals an erratic attention to ecological functions. While centuries of neglect were identified in the previous chapter as the cause for the Bièvre’s demise, recent efforts to reverse damages are constrained by continued urbanization. The projects that have been realized are commendable, but why hasn’t greater ecological functionality been achieved? The creation of the Union Renaissance of the Bièvre and Mixed Syndicate and collaboration between various public entities testify to the presence of a comprehensive approach. The charter and statutes laid out by the Union and the Mixed Syndicate show that clear objectives for the stream’s entire course have been developed. The lack of greater attention to ecological functions could merely be the nature of a very constrained urban fabric, overburdened with infrastructure that makes stream recovery extremely problematic. The added challenge of purifying numerous unidentified sources of waste water exacerbates the problem. Yet the mere definition of what is considered ecological can also be pinpointed. Ecological integrity, in the sense described in Chapter One, may not be feasible. The Plan Vert, or Green Plan, of 1995 outlined the creation of a greenway along a covered Train Grand Vitesse (TGV, Speed train) line running parallel to the Bièvre. While the stream’s restoration was considered a priority at the time, its future remained uncertain. The tracks for the TGV line already existed, making a greenway feasible here. Attention to the need for open spaces for recreation and air was paid, but the potential for creating an ecological stream corridor passed up.

Towards a Parisian Restoration

The Conseil Régional’s main research division, the Institut d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme d’Ile-de-France (IAURIF, Institute of Development and Urbanism of Ile-de-France Region, has been involved in many environmental projects, such as the Plan Vert, within the Bièvre Valley. Their regional approach to the Bièvre’s Parisian restoration will be compared in the next chapter to the city’s main research bureau, the Atelier Parisien d’Urbanisme (APUR). Both play important roles in defining the institutional context in which the Bièvre is found.

The following map shows segments of the Bièvre already being restored and those determined capable of restoration in the near future. Both the Massy-Verrières segment and the Parc des Prés in Fresnes are marked with red cross-hatching. (IAURIF)

Recent history in the Bièvre Valley testifies to the attention paid to creating a separate network for rain and waste water, creating opportunities along the Bièvre for recreation and natural habitat, and working towards its greater potential in the future to becoming a self-sustaining system in the most urbanized portions. Although urbanization continually threatens the Bièvre valley, a system is now in place to prevent the reoccurrence of past destruction, be it floods or overdevelopment of the streambed. The unification of communes and associations ensures this.

To uncover the Bièvre south of Paris is a colossal undertaking involving the purification of over 50 smaller streams that feed into the Bièvre Collector. Water quality below the accepted norms for open-air exposure poses an enormous task for restoration efforts from Antony to the Seine. The numerous outlets emptying wastewater into the Bièvre must be treated or eliminated before water becomes safe for public exposure. The progress made thus far is perhaps the best gauge for how the project will evolve for its final leg.

The rehabilitation of the Bièvre is a massive coordinated effort to protect the natural environment of the Bièvre valley, to improve the management and sustainability of its sanitation system, and to protect the best interests of those residing in the area. The continual efforts to preserve the natural environment from the expanding city have been effective in conserving land and in stimulating support to restore the Bièvre deeper and deeper into urbanization. Chapter Four will examine how this message has been interpreted by those working on the Parisian segment.